There Is Reason To Hope For Renewed Black-Jewish Relations

Black and Jewish Americans share theological and historical commonalities.

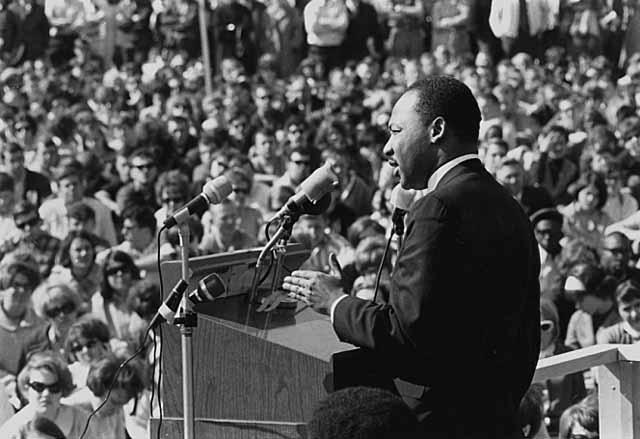

Wikimedia commons.

With Kanye West on the political right spewing anti-Semitic tweets, and Black Lives Matter on the intersectional left advocating the dismantling of the Israeli state, it is easy to despair over the state of Black-Jewish relations. Yet, in the quieter spaces behind the headlines, there are signs of a resurgence in the Black-Jewish alliance that was once a driving force behind the American Civil Rights Movement.

That landmark alliance was shaped by parallel experiences of oppression and exclusion. For a century, after the Civil War put an end to the institution of slavery, African Americans suffered further oppression throughout the country.

Black people in the northern states were excluded from well-paying jobs and desirable neighborhoods, while blacks in the Jim Crow south lived in constant fear of lynching and violence. Over that same period, more than two million Jews fled the Russian Empire for America, many traumatized by experiences during the “pogroms” that were similar to those endured by African Americans.

African Americans and Jews also share a common theological identity as “Exodus peoples.” While the Jewish escape from slavery is ancient history, it remains central to Jewish prayer and ethics: among the Torah’s most frequently stated commands is to be kind to the stranger, for you were strangers in Egypt. For African Americans, the Old Testament framing of both slavery and the long march to freedom is exemplified by the iconic spiritual “Go down Moses,” a refrain frequently heard during the pitched battles of the civil rights movement.

Hence it was no coincidence that black and Jewish leaders joined together in 1909 to found the NAACP, and again in 1950 to found the Leadership Conference on Civil Rights, which was responsible for drafting the original text of the 1964 Civil Rights Act.

Half of the volunteers for the 1964 “Freedom Summer” in Mississippi, who helped black citizens register to vote, were Jewish.

To be clear: the principal leaders and foot soldiers of the Civil Rights movement were courageous black Americans. But the record shows clearly that their most consistent allies in the fight for equal rights were Jewish Americans.

This alliance was by no means a one-way street. While American Jews experienced far less bigotry than their black allies in the Civil Rights Movement, their spiritual homeland of Israel faced constant existential peril. America’s black leadership responded to that peril by deploying the full force of its moral voice in Israel’s defense. Addressing a national Rabbinical Assembly in 1968, Rev. Martin Luther King announced: “Peace for Israel means security, and we must stand with all of our might to protect its right to exist, its territorial integrity. I see Israel, and never mind saying it, as one of the great outposts of democracy in the world.”

In November 1975, thirteen days after the UN adopted its notorious resolution declaring “Zionism is a form of racism,” the “Black Americans to Support Israel Committee” declared in a full page New York Times ad that “We support democratic Israel’s right to exist,” and contrasted Arab leaders’ intransigence with Israel’s “consistently demonstrated . . . desire to make concessions in the interest of peace.”

The Committee’s officers were three of the leading lights of the Civil Rights movement: A. Phillip Randolph, Bayard Rustin, and Lionel Hampton. The ad’s signers were a gallery of first-rank figures from the political, legal, cultural, and athletic arenas such as Coretta Scott-King, Julian Bond, Harry Belafonte, Hank Aaron, and Arthur Ashe.

So what went wrong? What sundered this landmark alliance? In sum: the growing division within civil rights advocacy between mainstream liberals and an increasingly militant left. From about 1965 onward, a new ideology emphasizing collective group rights, racial resentment, and rejection of allegedly “White” bourgeois norms grew increasingly prominent in America’s racial discourse.

And the leaders of the Black-Jewish alliance, who had so heroically turned the tide against the illiberalism of the far right, proved far less equipped to counter this new illiberalism from the hard left.

Militant leftism took hold both “in the field” and in the academy. Out in the field, the courageous battle for equal rights and respect led by Rev. King and his allies came to be scorned by a younger activist generation.

Newer groups like the Maoist Black Panther Party and the black nationalist Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee embraced violence and militant racial separatism. In their home base of Oakland, California, armed Panthers patrolled the streets, inciting violent confrontations with the police and shaking down black business owners for protection money.

The Panthers’ and SNCC’s militant, separatist ideology was far from representative of the views held by most working- and middle-class black Americans. Yet many white liberals – including prominent Jewish liberals – embraced such positions as “authentically Black,” culminating in such follies as the infamous 1970 Black Panthers’ fundraiser hosted by symphony composer/conductor Leonard Bernstein at his Manhattan townhouse. Many such liberals also chose to overlook an increasingly anti-Semitic component of the new leftist racialism.

The old alliance faced further strains as black separatists embraced “anti-colonialist” ideology, which refocused their priorities towards “third world” peoples emerging from colonial subjugation, while scorning America as irredeemably evil and denouncing Israel as a Western colonial enterprise.

The academy replicated and amplified this ideological shift, with ever more Professors both embracing and providing scholarly justifications for illiberal racialist thinking. New academic departments of Black Studies, Women’s Studies, and similar identity-based disciplines propagated and disseminated this ideology; and, despite attracting scarce attention outside the ivory tower, it gradually became the dominant analytical paradigm in campus liberal arts departments across the country, and, after 2020, society as a whole.

All the while, Rev. King’s prophetic call that his children be judged first and foremost “by the content of their character” was shoved aside, in favor of a repackaged version of the age-old tribalist concept that Race Is Destiny.

But with this illiberal ideology now holding center stage in America’s racial discourse, two intriguing counter-trends are becoming apparent.

First, and precisely because of its embrace by so many school administrators, opinion leaders, and corporate titans, the radicalism of the academy’s racial essentialism has for the first time become highly visible to the general public, which until recently paid scant attention to these ivory tower abstractions. The resulting public response to these radical ideas is evident in the wave of local parent groups challenging school diversity policies, which have reshaped curricula around the ideology of Critical Race Theory.

Second, the failures of and the harms occasioned by these ideologically-driven initiatives are also becoming more publicly visible through the work of a small but growing set of dissenting policy specialists and opinion leaders. This group includes scholars and writers like John McWhorter, Wilfred Reilly, Jason Riley, and Ian Rowe, whose books and essays conclusively refute the “systemic racism” explanation for Black-White disparities.

They and other like-minded scholars demonstrate that a combination of demographic asymmetries (e.g. the lower average age of Blacks vs Whites), higher fatherless rates, lower average per-student homework hours, and cultural pressures against “acting White” in parts of the black community account for most of the intergroup disparities in academics, income levels, and crime/arrest rates.

A similar rethinking is beginning to emerge in the Jewish community, challenging the widespread embrace of racialist ideology by many leading Jewish institutions. This rethinking is evident in the efforts of new groups like the Jewish Institute for Liberal Values and the Jewish Leadership Project, as well as in journals such as Sapir and White Rose. Among other things, these efforts have highlighted the tendency of racialist ideology, especially its binary “oppressors vs. oppressed” framing, to propagate both antisemitic stereotypes and annihilationist hatred of Israel.

This is where the basis of a reconstructed Black-Jewish alliance is being formed. And just as the prior Black-Jewish alliance succeeded in defeating the malevolent illiberalism of the far Right, so too will this renewed alliance counter the toxic illiberalism of the far Left.

To be clear: far Right racism and anti-Semitism still stalk the land, as starkly evidenced by such events as the 2017 “Unite the Right” rally in Charlottesville, and the 2018 Tree of Life synagogue shooting in Pittsburgh.

But thankfully, for several decades now, the far Right’s agents of hatred have been essentially marginalized in American society, and remain sequestered far from the levers of political, economic, and cultural power. Meanwhile, the far Left’s intersectional racialism has found a welcoming home amid those centers of power.

As in the past, this new effort to reclaim the liberal high ground from its illiberal opponents will be a generational struggle, waged not only by black and Jewish Americans but by all of us who value liberal democracy. After all, the liberal enterprise has benefited everyone in this country—it’s only right that we all come together to defend it.

The black-Jewish alliance of the 1960’s Civil Rights Movement offers a wealth of inspiration and lessons for our effort to overcome illiberal racialism today. With this alliance as a model and a starting point, we shall over come. Again.

Henry Kopel is a former federal prosecutor and author of 'War on Hate'. He writes for the Foundation Against Intolerance & Racism.